HENRY ELLIS, who had been appointed by the king lieutenant-governor of Georgia, was still a young man about thirty-six years of age. He had been a daring and skilful sailor in the Pacific Ocean and had received high honors in England. He landed in Georgia February 16, 1757, and waited upon Governor Reynolds at once. He was then taken to the council chamber, where he was installed as lieutenant-governor and acting-governor of Georgia during the absence of Governor Reynolds, who sailed for England the same day. The people welcomed him with bonfires and public parades. In the evening the houses were illuminated, and everybody rejoiced in the hope of a new season of prosperity. The lieutenant-governor was especially pleased with the address of a band of young soldiers who, to the number of 'thirty-two, had enrolled themselves under the command of their schoolmaster and paraded before his house.

The first care of Lieutenant-Governor Ellis was to provide for the defence of the colony. He obtained a ship of war and five hundred stands of arms to protect the coast. He tried by justice and mild measures to heal the discontent that Reynolds had created. 'He looked into every department of the government, and recommended a chief justice for the province. He visited the southern section, and favored the removal of the capital from Savannah to Hardwicke. He held a conference with the Creek Indians at Savannah, and by his tact secured their friendship and promises of peace. This was very important, as France and England were at war, and French agents had been sent among the Creeks to induce them to attack the English in Georgia.

When the legislature, or General Assembly, met, June 1757, the governor made an opening address full of good wishes for the welfare of the colony. Among the bills passed by this legislature was one offering the Province of Georgia as a home for debtors who could not pay what they owed. Here they could find work and lands, and gradually save enough to pay their debts.

The rapid growth of the settlements on the Medway River impressed the people of that district with the necessity of having a port of entry of their own from which their crops could be shipped and where supplies for their plantations could be bought. On the 20th of June 1758, Thomas Carr conveyed to five trustees three hundred acres of a grant, which he had received a year before from the king, to be laid out by them as a town called Sunbury. The trustees were men of prominence, and two of them, John Stevens and John Elliot, were influential members of the Midway Church. The site selected for the town was twelve miles from the ocean, on a beautiful bluff on the Medway River, covered with magnificent live oaks and magnolias. A more beautiful spot could not be found in Georgia. The town was laid off into streets, wharves were built, and it soon became a place of great importance in the colony, second only to Savannah. Its principal trade was with the West Indies and the northern colonies.

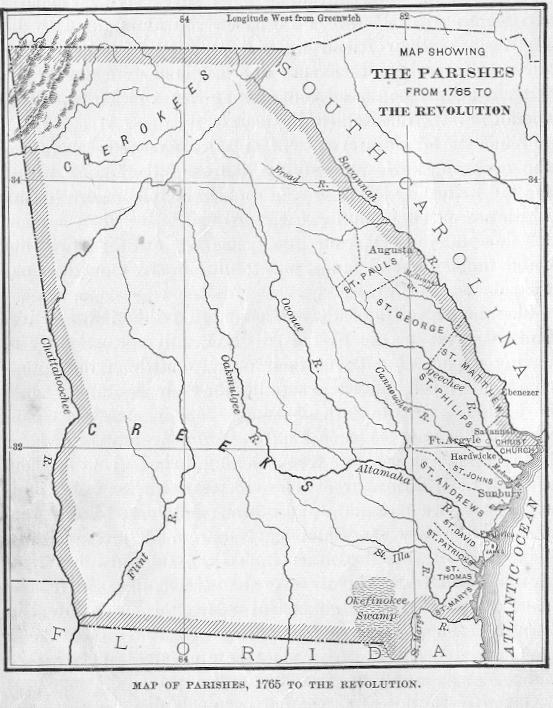

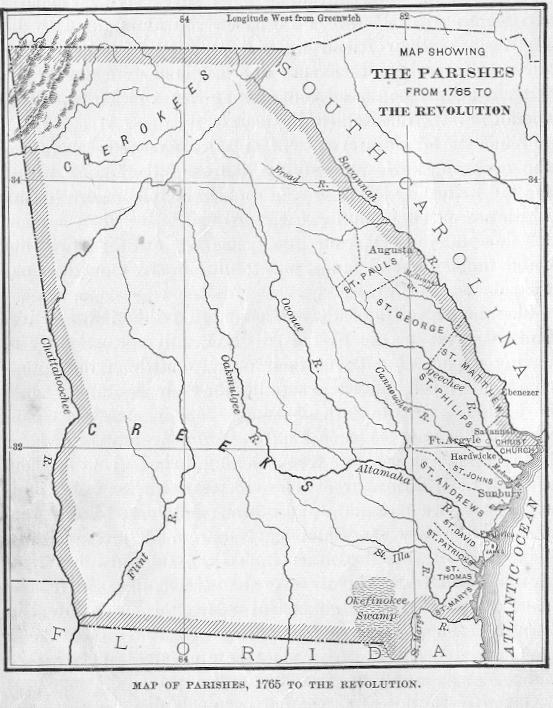

In 1758 Georgia was divided into eight parishes: Christ Church Parish, including Savannah; St. Matthew's Parish, including Ebenezer; St. Paul's Parish, including Augusta; St. George's Parish, including Halifax; St. Philip's, including Great Ogeechee; St. John's, including Midway and Sunbury;

St. Andrew's, including Darien; and St. James', including Frederica. These divisions were made in order to better regulate the government of the colony. The law provided for the holding of public worship in each of these parishes. In 1765 four new parishes were added to the number then in Georgia. They were St. Patrick's, St. David's, St. Thomas', and St. Mary's, and they were all between the Altamaha and the St. Mary's rivers. These parishes were really counties.

In 1758 Governor Reynolds, who had gone to England for trial, was removed, and Lieutenant-Governor Ellis was commissioned "Governor-in-Chief of the Province of Georgia," an honor he fully deserved. During the same year the colony sent over to England twenty-five thousand pounds of indigo and fifty-five hogsheads of rice. Georgia was steadily growing in population, commerce, and importance.

The wisdom of Governor Ellis in making fast friends of the Creek Indians was apparent in 1759, when the Carolinas and Virginia became involved in war with the Cherokees, a most powerful tribe. Their lands covered all North Alabama and North Georgia and much of South Carolina and extended north to the Ohio River. Their warriors had assisted the English attack on Fort Du Quesne, where Pittsburg now stands. After the capture of this fort, the Cherokee warriors returned home through Virginia and carried off some horses that they found pasturing in the woods. They were followed by a party of Virginia frontiersmen, and twelve of their number were killed and the others captured. This injustice aroused the young warriors of the whole Cherokee Nation, and, instigated by French agents, they began attacks on the Carolina frontiers. On the Little Tennessee River, in the valley beyond the mountains, was Fort Loudoun, and in South Carolina, near the town of Keowee, was Fort Prince George, both in the Cherokee country. Fort Loudoun was surrounded by the Cherokees and the garrison cut off from all supplies.

Governor Lyttleton, of South Carolina, called out the militia and prepared to march against the Cherokees. Thirty-two chiefs, hearing of this, went to Charleston to make peace; but the governor refused to listen to them, and forced them to march with his army to Fort Prince George. He put guards over them on the march, and confined them when he reached the fort. This unjust treatment was a great outrage. Finding his army not strong enough to attack the Cherokees, the governor now concluded to make peace with them, so that he might return with credit to Charleston. He sent for Attakullakulla, a wise old Cherokee chief, who was a friend of the English, and with his assistance peace was arranged. Twenty-two Indians were to be held in the fort as hostages for the surrender of the twenty-two Indians who had been murdering the whites, and the governor returned to Charleston.

Governor Lyttleton's treatment of the chiefs had aroused a spirit of revenge, and before he reached Charleston, they had killed fourteen men and besieged the fort. Unable to capture it, they decoyed Captain Cotymore and two lieutenants out from the fort and murdered them. In retaliation, the soldiers in the fort attempted to put the hostages in irons. One of them resisted and stabbed a soldier, whereupon they were all murdered. This act again aroused all the Cherokee warriors, and they at once began to murder the settlers along the frontier of South Carolina. Smallpox had broken out in South Carolina, and the militia could not be called out. General Amherst sent Colonel Montgomery from New York with a force of regulars and seven troops of Rangers from North Carolina and Virginia. He at once attacked the Cherokees in South Carolina, burned several of their towns, killing men, women, and children, and drove them to the mountains. Here he attempted to follow them, but he was drawn into an ambuscade and narrowly escaped defeat. He saw that he could do nothing against them in the mountains with his small force, so he returned to Charleston and thence to New York.

On August 7, 1760, the garrison at Fort Loudoun, cut off from supplies and being on the point of starvation, was forced to surrender. The Cherokees promised that the garrison should be conducted in safety to Fort Prince George, but the first night of the journey the soldiers were attacked and many of them were killed. The others were carried back to Fort Loudoun as prisoners. The British Government now recognized that the Cherokee war was a very serious matter, and prompt steps were taken to end it.

Meanwhile Governor Ellis was preparing to leave Georgia. The climate did not agree with him, and he had applied, a year before, for permission to return to England. This had been granted, but he was forced to wait for the arrival of the lieutenant-governor, James Wright, who had been appointed to relieve him.

[Governor Henry Ellis was born about the year 1720, and was distinguished at an early age for his study of the natural sciences and by his interest in geographical discoveries. When he was twenty-six years of age he was entrusted with an expedition to find a new route to the Pacific Ocean, and was offered £20,000 if he succeeded. With two ships he set sail and entered the Straits of Hudson. For over a year he tried to find his way through, braving the dangers of new seas and a severe winter. He returned to England in 1747, and was at once made a Fellow of the Royal Society. He was soon after appointed lieutenant-governor of Georgia. He was spoken of as "an active, sensible, and honest man."]

[Governor James Wright was descended from an ancient and honorable family. His father had settled in Charleston, where he married, and afterward became Chief Justice of South Carolina. James Wright was born in Charleston, but educated in England. Upon his return to Carolina he began the practice of law, and was appointed attorney general of the Province when only twenty-five years of age. When he entered upon his duties as governor of Georgia he was about forty-six years of age, in the prime of his life, a firm and loyal adherent to the Crown, and ever true to the trust imposed upon him in the trying times of the Revolution soon to follow.]

[The way in which the Indians were received at Savannah when Governor Ellis made his treaty with them in 1757 is shown by the following account;

"The Indians were escorted by Captain Milledge with his troop of Rangers, and approached the town. They were met in an open savanna about a mile distant by Captain Bryan, with the principal inhabitants of the town, on horseback, who welcomed them in the name of his Honor the governor, and regaled them in a tent pitched for that purpose.

"The Indians were conducted to the council, and were introduced to his Honor the governor, who, holding out his hand, addressed them in the following manner: ' My friends and brothers: Behold my hands and arms! Our common enemies, the French, have told you they are red to the elbows. View them! Do they speak the truth? Let your own eyes witness. You see they are white, and could you see my heart you would find it as pure, but very warm and true to you, my friends. The French tell you that whoever shakes my hands will be immediately struck by disease and die. If you believe this lying, foolish talk, don't touch me. If you do not, I am ready to embrace you.' Whereupon they all approached and shook hands, declaring the French had deceived them in this manner."]

There were 1415 visitors, at our previous host from 23 Jun 2004 to 9 Aug 2011.

© Copyright 2003 - 2015 - Tim Stowell